I have 5 thoughts to share with you from this week’s

study:

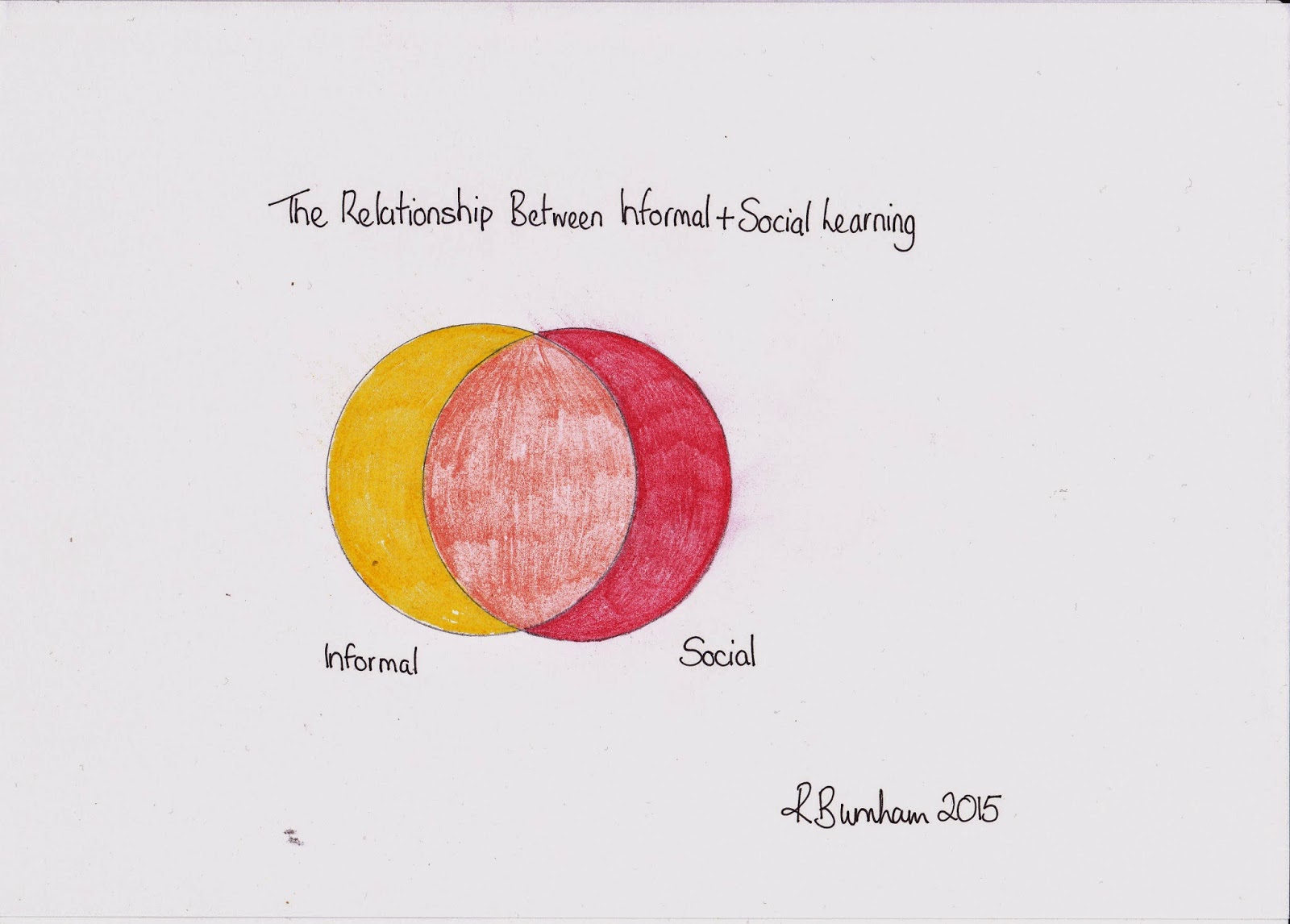

1. The Relationship Between Informal & Social Learning

There is a big overlap between social learning and informal learning. When I use the term ‘informal learning’, I refer to all those learning methods which are outside of formal learning or education. A great many of the methods of learning that we describe as informal learning involve social learning ie learning with and from other people. I recently wrote a blog about informal learning which included a diagram attempting to categorise a range of informal learning methods and if you read the blog, just how many of these methods do also fall under the heading of social learning. This is one of the factors in the confusion that surrounds these terms.

2. The Relationship Between Informal, Social and Formal Learning

The challenge for L&D professionals is to work out how we can most effectively support, encourage and enable informal & social learning in our organisations. To do that we need to be clear about when each of formal, informal and social is most effective. It is about making effective choices to suit the context.

We can also combine these through designing scaffolded or guided blended learning programmes as Jane Hart describes them, which combine aspects of the structure of formal learning with the openness, flexibility and individualised nature of informal learning. Providing access to curated collections of resources which learners are encouraged (but not required to access) can be part of this. Such programmes can also incorporate opportunities for informal social learning eg through sharing of resources (co-curating) & sharing information/tips/ideas/experiences perhaps through the use of social media.

3. Understanding the Value of Social & Informal LearningIt is helpful to appreciate the distinctive benefits of each type of learning to know how best to make use of it.

Social learning brings with it:

· Access

to information & expertise in a timely fashion

· Different

ideas/experiences

· Alternative

perspectives

· Opportunity

to question & be questioned

· Opportunity

to work co-operatively with others on common issues or problems

The main downside to social learning that I have become aware of is a risk of ‘groupthink’ developing, particularly in social learning environments where there is an absence of critical thinking. Two factors can particularly affect this I think: social learning in contexts where there is a lack of external contact and secondly, where there is limited engagement with theory.

In the first case I am thinking about the situation that arises in some organisations where the organisation is very inward facing, perhaps working in silos internally and then further exacerbates this by limiting opportunities for contacts & networking. This can come in the form of reduced budgets for travel, limited opportunities to step away from operational duties even for short times, discouragement of the use of social media for work use or even an organisational culture that emphasises the distinctiveness & uniqueness of the organisation. I have experienced this kind of environment occasionally when providing an in-house programme for L&D teams – a culture can develop where social learning leads to the development of clones, where a single idea of ‘best practice’ can be arrived at & then stuck with and a lack of challenge flourishes. (Just to be clear - I am currently working with an in-house team and my experience is very different with this present team, but this is why I was so keen for each member of the team to have access to a mentor from outside of the organisation.) I think for social learning to be healthy, we need access to a diverse network.

Secondly, for social learning to be healthy and not just some kind of collective folk wisdom, it needs to be tested against theory and particularly evidence based research. Our practice needs to be informed by theory and the theory needs to keep pace with & in turn be informed by practice – ie we need to explore praxis rather more consistently than we often do.

@conmossy shared a very relevant quote as a result of the Twitter Chat on 18/2/15 by Kirk

‘the possession of knowledge

without the capacity to effect professional actions of various kinds is

pointless; professional action that is not informed by relevant knowledge is

haphazard; and knowledge and skills that are not subjected to self-criticism

constitute a recipe for professional complacency and ineffectiveness.’ (Kirk, G ‘The Chartered Teacher: A Challenge

to the Profession in Scotland’ Education

in the North, 11 10-17, 2004)

5. Social Learning is great, but don’t forget individual learning

In exploring and appreciating the huge value of social learning, let’s not forget that individual learning has its place and value too. There are many forms of informal learning that are about individuals learning – on their own, at their own pace, thinking their own thoughts and experimenting & reflecting. Donald Clark in his blog ‘9 Reasons Why I am Not a Social Constructivist’ reminds us of the value of individual learning and also of its particular importance to introverts. Perhaps I should own up here to my own introversion and how much I enjoy & need time and space on my own as part the way I learn most effectively.

Sometimes social learning experiences, whether traditional formal approaches or informal approaches can feel rather ‘fast food’ approaches to learning – with their speedy give & take and sometimes little opportunity to slow down, ponder, question and pause. In those circumstances, I know I struggle sometimes to share deeper reflections or to think critically.

I think there is a value in more of a ‘slow food’ approach to learning from time to time. The ‘slow food’ movement is all about food that is cooked from scratch, often using traditional slower cooking methods such as ‘braising’ ‘marinating’ and ‘oven-roasting’, with fantastic fresh locally produced ingredients. Actually in learning terms, including asynchronous social learning methods, such as discussion forums, which naturally enable opportunities for pause and reflection can be a ‘slow food’ method.

Adopting more of a ‘slow food’ approach doesn’t mean abandoning social learning, but adopting more of a balanced diet between social and individual learning. The precise proportions may vary from individual to individual – introverts among us may prefer a slight higher proportion of individual learning, to the extroverts in the population, but we all need both approaches, I would suggest.

Or we could explore the ideas suggested by Andrew Jacob’s 'Silent Disco' blog and find ways for individual learning at its own pace, but within a social context. I think that is what we do with blogging – people share their learning individually but by sharing our blogs and then reading & commenting on others we are subtly influenced and learn together.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and ideas – and feel free to take some time to ponder on them if you would prefer!

Rachel

Burnham

23/2/15

Burnham L & D Consultancy helps L&D

professionals become even more effective. I am particularly interested in blended

learning, the uses of social media for learning, evaluation and anything that

improves the impact of learning on performance.

Follow me on Twitter @BurnhamLandD